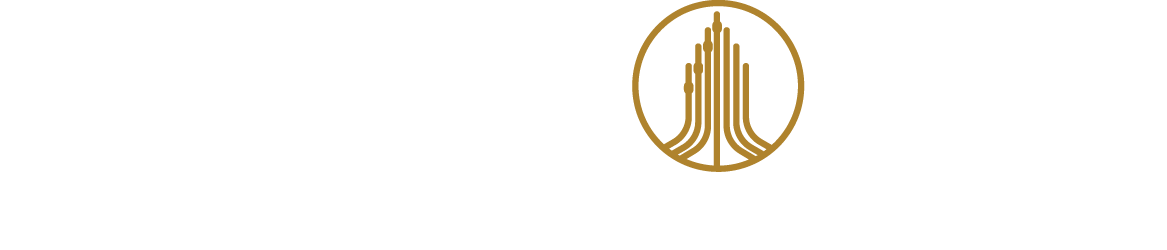

Botswana’s diamond money is drying up, and that’s putting pressure on the government’s budget. Most people with bank loans rely on government salaries to pay them back. But if the government runs low on cash and delays salaries, people can’t pay their loans, and banks suffer. It’s like Warren Buffett said: “You only see who’s swimming naked when the tide goes out.” Right now, the diamond tide is going out. Is your bank ready?

If Botswana’s economy were a big three-legged pot, one leg would be diamond money. Another is government spending. The third? You, the average Motswana with a bank loan, mostly backed by your salary.

But what happens when that first leg, diamond revenue, starts to shake, as it is now?

This question came up during a recent Public Accounts Committee hearing, where the Ministry of Finance laid things bare about the tough balancing act the government is facing: trying to manage falling revenues while still meeting its financial promises.

The government is struggling to keep up with spending. But the Permanent Secretary to the Ministry of Finance, Dr. Tshokologo Kganetsano, insists that the government, as the single largest employer, must keep paying civil servants.

His answer was blunt: The government is the biggest employer, pointing out that over 130,000 people are on its payroll.

Why?

According to the Financial Stability Report from October 2024:

- Most of the money banks lend out goes to people, not businesses. In fact, 64% of all loans are taken out by households, ordinary people like you and me.

- Of those household loans, the biggest chunk, 68%, are unsecured loans. That means loans without any security or property put up as collateral.

- These types of loans are more expensive and risky. The report warns they could become a problem if interest rates suddenly go up or if people lose their jobs. It could push many into debt trouble.

“You fail to pay salaries one month; they fail to service their loans. That’s the collapse of the financial system,” Dr Kganetsano said during the PAC.

In essence, the fear is that if the government delays salaries, it could trigger a domino effect:

- People can’t repay their loans.

- Banks start recording losses.

- Credit becomes harder to get.

- The whole financial system starts to wobble.

Botswana has long depended on diamonds to fund its needs.

What’s new?

Debswana announced the implementation of targeted measures to preserve long-term business sustainability and operational resilience.

As part of these measures, Debswana will scale back production volumes to 15 million carats in 2025 as follows:

- A temporary three-month pause in production at Jwaneng Cut 9, covering the May to July 2025 production months.

- A combined temporary pause at the Orapa Mine Pit and Orapa No. 2 Plant during May, June, and October 2025. Notably, the May and June production pause at Orapa No. 2 Plant coincides with its scheduled annual maintenance shutdown, thereby extending the maintenance into a strategic production halt.

Economic think tank, Econsult, commented:

“No mineral revenues for government of Botswana for a while.”

This isn’t just about government. It’s about your bank too.

That brings us to Warren Buffett’s famous quote:

“You only find out who’s swimming naked when the tide goes out.”

What Buffett meant is this:

When times are good, it’s easy to look like you’re doing well. But when things get tough, like when money runs dry, that’s when we see who was really prepared. Weaknesses that were hidden during the good times suddenly come to light.

So, who is swimming naked?

In this story:

- The tide: Diamond money drying up.

- Swimming naked: Banks exposed to civil servant loans.

- The rescue: Government, still paying salaries, even with little money left.

State Of Play

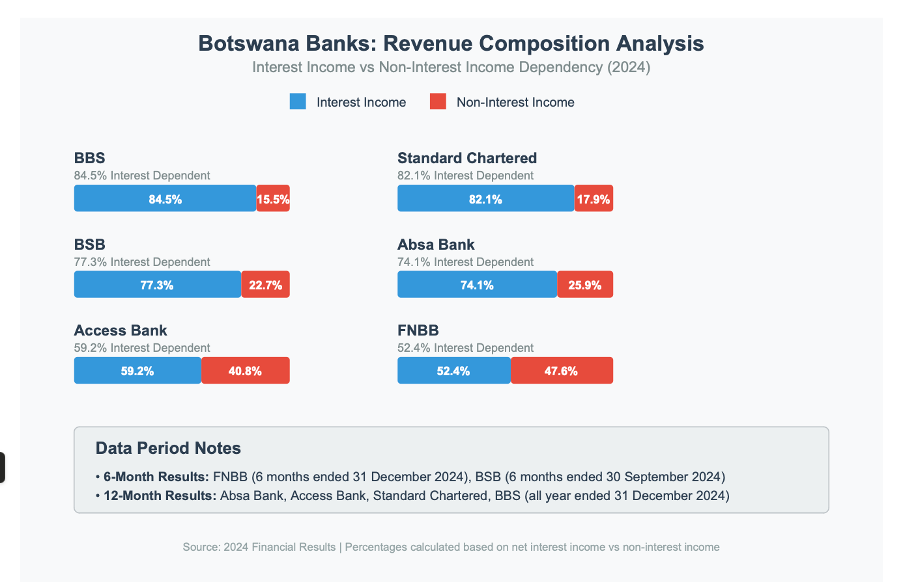

- Most Botswana banks rely more on interest income than fees, meaning their revenue depends heavily on borrowers paying back loans.

- BBS and Stanchart are the most exposed, with over 80% of income coming from interest.

- FNBB is better diversified, with almost a 50/50 split between interest and non-interest income. That gives it more cushioning in tough times.

- Two-thirds or more of the income comes from loans for Absa and Access Bank.

So what’s at stake?

- For banks: A wave of defaults if salaries are missed.

- For investors: Lower dividends, slower growth, or worse.

In its balancing act, Kganetsano said:

“We will play the chess, whether we win or not is another matter.”

Living Hand to Mouth

- Between January and the end of May, Dr. Tshokologo said the government took out two short-term loans on top of the P6 billion it received from SACU. All that money is already gone.

- On Monday, 6th January, P6 billion hit the government’s account. By the end of Thursday that same week, over 90% of it had been spent.

- On the day of his presentation, Dr. Tshokologo said that when he walked into the PAC, there was about P3.5 billion left in government savings. Just hours later, P2.8 billion of that was used to pay off loans.

This illustrated how:

“We borrow to fund current consumption,” said Kganetsano.

Private Companies Feel the Squeeze

But it’s not just about banks and civil servants. Domestic economic activity plays a big role too.

Botswana’s diamond revenues don’t just pay government salaries, they also decide whether suppliers get paid on time.

During the hearing, it came out that some suppliers haven’t been paid, and that’s starting to hurt private companies. When a business doesn’t get its money from the government, it struggles to pay its own workers and bills.

The truth is, government spending keeps money moving in the economy. When the government pays businesses, those businesses pay their staff, buy stock, and keep the wheels turning. If that spending slows down, the whole system feels the squeeze. Even down to a hawker.

Dr Kganetsano, the former Bank of Botswana deputy governor, warned that if economic activity continues to slow:

- Companies may lay off workers,

- Profits shrink,

- And like individuals, businesses may start defaulting on their own loans.

It’s a chain reaction: fewer diamonds, less government money, unpaid suppliers, job cuts, loan defaults, pressure on banks.